The number of people submitting DNA samples is rising, with a corresponding rise in the number of people on forums reporting that they have been asked by the test company to submit another sample.

AncestryDNA say in their FAQ that:

During the testing process, each DNA sample is held to a quality standard of at least a 98% call rate. Any results that don’t meet that standard may require a new DNA sample to be collected.

A call rate? I don’t see that term explained elsewhere in their FAQ so I thought it worth a blog post on how the companies determine that a particular kit doesn’t meet their quality standards. As well as “call rate”, I’ll explain a few other terms along the way.

When the test lab receives your DNA sample, they do not analyse the entire collection of DNA in your swab or spit. The technology right now doesn’t scale up to deal with every gene. Instead, your sample is broken down to identify a set of very specific positions within your chromosomes.

We humans are basically the same as each other across 99.9% of our DNA sequence. That means that at many positions your DNA will be identical between you, your sister Sally, and that guy who delivered the kit to your door. Unless “that guy” is also your brother, then most parts of your DNA sequence will not allow the lab to distinguish between your siblings and strangers at the door.

We humans are basically the same as each other across 99.9% of our DNA sequence. That means that at many positions your DNA will be identical between you, your sister Sally, and that guy who delivered the kit to your door. Unless “that guy” is also your brother, then most parts of your DNA sequence will not allow the lab to distinguish between your siblings and strangers at the door.

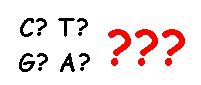

Instead, the testing companies target positions where there is likely to be genetic variation within our species. These variants at a particular position are known as Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms, or SNPs for short. Don’t worry too much about the mouthful, but be aware that there are only four types of nucleotides and they go by the code names of A, C, G or T.

You’re probably familiar with the DNA helix, so where do these codes fit into it? In this picture of chromosomes, there are two long strings coiled around each other. Each string is a sequence of nucleotides: A, C, G or T, in a particular order.

You’re probably familiar with the DNA helix, so where do these codes fit into it? In this picture of chromosomes, there are two long strings coiled around each other. Each string is a sequence of nucleotides: A, C, G or T, in a particular order.

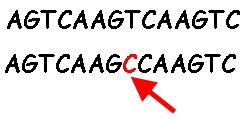

So lets take the sequence AGTCAAGTCAAGTC. You and big sis Sally share that sequence. But what about the delivery guy? His sequence is AGTCAAGTCAAGTC. Is it the same?

Let’s line them up to see:

One nucleotide at a particular position is different between you and that guy.

One nucleotide at a particular position is different between you and that guy.

Suppose we looked at the same sequence for the delivery guy’s brother. it would probably have C instead of T too.

But wait! It might not. The delivery guy and his brother could have inherited the DNA at that precise position from different parents. Or they could differ due to the random shuffling in DNA during reproduction. Due to inheritance and random variation, the labs need to test hundreds of thousands of alleles to let statistics take over and make us confident that we can use use the average variance across SNPs to determine how much we match our siblings versus our non-relatives.

Identifying the nucleotide code of each SNP is known as “calling” the SNP.

Now, here’s the problem. Sometimes the lab equipment cannot identify the nucleotide code. This can be due to contamination, or to equipment error, or to the way that DNA is broken down for the analysis.

If an SNP cannot be identified, this is known as a “no-call“.

The overall call rate of your DNA sample is the number of SNPs that were coded divided by the total number of SNPs that the lab tried to code. So if 2% fail to be coded then the kit will probably be retested, and if it continues to fail, you will be asked to send a new sample. Yep, that’s the delivery guy back at the door: