This article is on how to enter names into your tree in ways that give you the most benefit from Ancestry.

Let’s start by saying that naming guidelines aren’t about foisting obscure and annoying rules on tree owners. It’s about giving:

- You the best chance of remembering how and why you noted facts in your tree

- Others the best chance at spotting connections and reaching out to you

- Ancestry Search the best chance of finding records relevant to your tree.

Name Variants, Name Changes, and Alternate Names

You’ve been working away on an ancestor and this is what you’ve found:

Joe Parks in one census is Joe Park in the next. His baptismal cert has his first name as Thomas. Joe’s headstone says Joseph (Thomas) Park. But a DNA match told you her family always called him Buddy.

Before we grapple with how best to record our ancestor, let’s nail down some terminology. Yes, let’s put names to the different ways of having different names.

Name Variants

Name variants are different versions or spellings of a name, with Smith/Smyth/Smythe being a classic example. Sometimes variants are simply misspellings by the record takers, with several versions of a name on the same court document.

Maggie, Meg and Molly aren’t so much different spellings as commonly used versions of Margaret. These are also known as variants.

Name Changes

Name changes are when a person is recorded with a different name due to a historical event. This could be during immigration, political upheaval, or changes to a family structure such as adoption.

Alternate Names

Nicknames are a form of alternate names. These are names that seem to bear no relation to the name at birth. I was trying to think of famous nicknames, and for some reason Curly from the Three Stooges came to mind.

The Stooges are a great case study!

Curly was born Jerome but was called Babe as the youngest in the family. When his brother Shemp married a lady also known as Babe, the family took to using his stage name – Curly. This brother was born Samuel. Their mother called him Sam in such a strong Litvak accent that it sounded like “Shemp”.

If you’re ever unsure of what nicknames are derived from a particular formal name, check out our massive list of nicknames that you may find in old documents.

Options for Recording Names in Ancestry Trees

Here are a few name entries I’ve grabbed from three trees. Each tree editor has chosen to use the basic name fields to record variants or alternate names.

The first entry has “Park or Parks” stuffed into the “Last Name” field. Using the “First and Middle Name” box to add a variant is more common. These tend to be marked with quotes or parentheses.

It took me at least three months of using Ancestry to notice there are other ways to enter names, aside from the Quick Edit box.

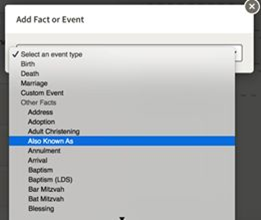

Open the profile of the entry and click on the +Add button in the Fact section.

“Also Known As” is near the top, but you don’t just get one option. Scroll well down to see plain old “Name”.

If you’d like to define your own name-changing event, perhaps a political upheaval, you can create a “Custom Event” from this interface.

Also Known As (AKA) vs Name

My general impression is that Ancestry users tend to choose the “Also Known As” event over the “Name” event. So what’s the difference between these choices?

The “Name” event allows you to record more detailed information. You can specify whether this is an Alternate or Preferred name. You can also add sources to this event.

Personally, I’m not so thorough but Ancestry is catering here for the more meticulous genealogists.

General Ancestry Name Guidelines

We’ve seen its perfectly possible for an individual to have five differing names from alternative sources. When entering that person into your tree, you should pick one version as the primary name. The rest become alternate names.

And to recap, these are the more commonly used options I’ve seeen for entering differing names:

- “Also Known As” fact

- Name” fact

- Custom Event fact

- stuff variants of first names into the “First and Second Name” field

- stuff alternate names into the “Last Name” field

- use the Suffix field

If you browse through some Ancestry videos, you’ll see that they prefer usage of the addtional facts feature to enter differing names. But the latter three options are very much out there “in the wild”.

None of these are “invalid” options. Your tree, your rules. But are some options more likely to bring added benefits to your research? And are some options likely to hinder your research?

Let’s run through some Ancestry name guidelines that are aimed at getting the maximum benefit for your research.

Be Consistent

The main advice is to be consistent across your tree. Don’t use “Also Known As” for one sibling’s nickname and add the other sibling’s nickname into her first name field.

Why? Because you’ll end up confusing yourself as to where and why you recorded the information.

Use Birth Records For The Primary Name

What to do with my example of census Joe, baptized as Thomas, and commonly referred to as Buddy?

What to do with cousins Maggie, Molly and Meg – all named after their great-grandmother Margaret?

The consensus is to start by entering the name on the birth record where available. Then use one of the additional methods to record the variants, alternates and name changes.

What about legal name changes?

The consensus is to use the birth record. In these cases, consistency helps communication. Suppose you decide to use the changed name of an ancestor, but a DNA match prepares her tree with the name at birth. You could be examining each other’s trees and passing like ships in the night.

With No Birth Record, Use The Earliest Reasonable Record

When a birth record cannot be sourced, then use the name on the earliest reasonable record.

I say “reasonable” because some judgement is called for, particularly if a census record is the earliest on offer. If you think there’s a good chance of a spelling or transcription mistake, then use the next source by date.

Treat Census Records Carefully

Be cautious with early census records if you can’t source a birth record. Many of the earlier generations could not read or write, so the recorded name is a version chosen by the census taker or perhaps a neighbour. The next census may show a different version by a different census taker, so which is “right”?

And regardless of literacy, there was far less emphasis or need for consistent spelling of names before the twentieth century. Your ancestors may have happily used different variants in different contexts.

Use Title Facts For Titles

I see a lot of “Fr.” And “Msgr.” entered in the “First and Middle Name” fields of Irish ancestry trees (denoting the clerical titles of Father or Monsigneur). But Ancestry provides a “Title” fact, and the general advice is to use it.

These titles are not present at birth and, like the Fr/Msgr example, can change over time. So they are not really part of the name. You can also add citations and dates with the Title event.

Take Exception!

I put my hands up and say I do not always follow these Ancestry name guidelines. When I started building out my tree, I was researching a branch with large numbers joining the clergy at each generation. When I’d return to my research, I’d scan my eye over the tree and spot males for whom I hadn’t entered a spouse or children.

Ah, I’d say to myself, I haven’t got to this individual yet. I must roll up my sleeves and pound the keyboard.

Only to find that I had indeed investigated and added their clerical titles as a fact, which of course isn’t visible until you click into an entry. To stop myself from continually clicking on these entries, I stuffed “Fr.” into the first name field.

Another solution here might be to upload some kind of clerical picture to each entry. But personally, I’m not a big fan of tree icons.

So if these guidelines would more hinder than help your research, do what works for you.

Use Birth Name, If Known, For Adopted Persons

This falls under the heading of legal name changes, but I see inquiries about it so often that it’s worth separating out.

If you’re an adopted person exploring your genetic heritage, then use your birth name as the primary name entry in your linked searchable tree. Let Ancestry’s automated search processes go to work for you.

Married And Maiden Names

The golden rule is to enter the maiden name for married women. This simply follows on from the general guideline of using the name recorded at birth. But it’s worth a separate section because it’s a common question and an oft-repeated mistake.

I think many people know this rule, but there are times when a record hint will provide the married name only. This happens particularly with “find a grave” type sources, and tree editors may blindly accept the hint. If you notice you’ve done so in a research session, this is a good sign that you’re working on autopilot and are probably fatigued. Double-check what else you’ve accepted into your tree, and then take a break.

There are exceptions to this guideline of course. For example, in Norwegian genealogy the concept of maiden names is fairly recent.

It’s unfortunately common to have difficulties finding maiden names. So what if you only know the married name?

Personally, I leave it blank. Sometimes I know the wife’s married name and don’t know the husband’s first name. I’ll create a husband entry with blank first name, and wife entry with blank last name.

Crista Cowan, the barefoot genealogist, enters a series of underlines – which is purely to help formatting her printouts of family trees.

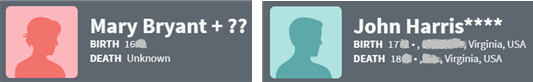

I do advise against setting up entries like the one above. The tree editor is probably recording that the maiden name is unknown and the married name has been entered.

Although the intent is clear to someone reviewing the tree, this will simply mess up Ancestry’s automated search routines and drive hints for women born Mable McCoy your way.

Variants In The “First And Second Name” Field

Stuffing nicknames and alternate names into the “First and Second Name” field is common. I’m talking about entries like these:

Purists will prefer to keep this field solely for what is entered on birth registration and use additional facts for the variants.

For me, the question is: does this format stop Ancestry Search from matching with indexed records? Will Ancestry guide you towards records with first name as Frances and surname as Patrick?

A little bit of experimentation shows that the Search is clever enough to find good records. We can assume it is grabbing the first word in the field and using this for a first name match with records.

We still want to get a narrowed search if we enter a genuine second name into this field e.g. matches for James Howard Carter, not just James Carter.

My tip here is that if you do want to add nicknames and variants into this field, have a clear demarcation as shown in the examples – quotations are parentheses are most common.

Avoid Alternate Names In The “Last Name” field

The tree editor in this example has entered a Last Name of “Park or Parks”.

The consensus would be that this is not appropriate use of the Last Name field. The best route is to pick one surname and source, and then add the second as an alternate fact with source(s).

Otherwise, your fellow researchers must guess at your intent when recording this detail. Have you seen both variants on different documents? Are you peering at a single document, unsure as to whether that’s an “s” at the end of the word or a fountain pen blob?

Avoid Custom Annotations In Name Fields

Here’s some examples of what I call custom annotations:

My guess is that the first tree editor isn’t sure whether Bryan is the correct surname.

The asterisks in the second entry mean something special to the tree editor, but I haven’t got a clue. Some tree owners I’ve questioned use asterisks to denote known DNA matches. Some use asterisks to remind them to follow up with more research.

Obviously, this hinders communication with other researchers.

But how does Ancestry Search cope with these extra characters?

Sometimes you’ll be okay. A little bit of experimentation suggests that Ancestry will strip out these non-alphabet characters and look for “Bryant” or “Harris”. I personally wouldn’t chance interfering with what should be a straightforward text matching process.

But sometimes things can go very astray. A case in point:

A Case Study With Custom Annotations

I see entries like this in plenty of trees.

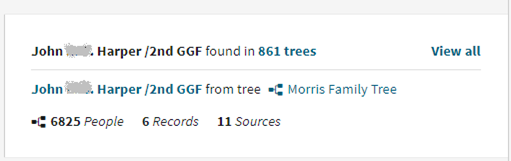

In this case, the last name includes “2nd GGF” which presumably reminds the tree owner that this is a great-great-great grandfather.

How will Ancestry Search deal with a surname entry of “Hay 2nd GGF”?

I created a private unsearchable tree with an exact copy of this tree entry, and then I hit the search button. Interestingly, the census and Find-A-Grave matching records looked correct. Ancestry must have stripped the words after the first space in the surname and looked for matches to “Hay”. So the tree owner does get a good Search experience.

But the original public tree with “Martin Hay 2nd GGF” did not show up in the first page listing family tree hits. The first two tree matches were private trees for a “Martin D. Hay”. The next tree match was for John Hay with similar dates and locations.

And here’s the kicker: the fourth listed tree match:

Yes, our “Martin Hay 2nd GGF” got a top match with “John Harper/2nd GGF”. I’ve actually obscured two initials included in John’s first name, which should really make this less likely to match. The “2nd GGF” is what’s driving this result.

To be fair to the power of Ancestry Search, I had better results with testing with a longer name. Something like “Martin Henderson 2nd GGF” was more likely to match with the original tree.

Nevertheless, the takeaway from this section is this: using these personal extra name parts may not stop your own searches from finding the right records. But it reduces the chance of other researchers finding your tree and reaching out to you.

Repurposing The Suffix field

For completeness, I’ll finish off on a common enough practice – stuffing alternate surnames into the Suffix field. For those who like this practice, the assumption is that Ancestry Search ignores whatever is in the suffix, so it doesn’t mess up record-matching.

That’s probably correct at the time I post this article. With the massive and growing volume of indexed collections, the Search process most likely ditches some fields – or your searches would take hours to complete. The suffix is a great candidate for throwing overboard. But who’s to say that technical advances won’t bring this field back into play?

In general, I advise against using fields for different purposes than meant by the software creators. It’s simply too hard to predict unintended consequences. But hey, I think this one is low risk.

More Articles?

We have two companion articles with tips on formatting dates and locations in your Ancestry tree.

The name entry chapter was critical for me. At age 17, my grandfather changed his F M and L names to completely new names. (Even my gma only knew him by those new names until after he passed!).

So this is very helpful.

Very helpful! Thank you.

Good to hear, Deborah!

So far so good.

I think the line “My guess is that the first tree editor isn’t sure whether Bryan is the correct surname.” should have a ‘T’ at the end of Bryant

No need to publish this one

Hi

I think the line “My guess is that the first tree editor isn’t sure whether Bryan is the correct surname.” should have a ‘T’ at the end of Bryant

No need to publish this one

So my father was legally adopted. In my tree I have his birth name attatched to him. How do I place my last name? My birth name (his adopted name), or his birth name?

The general advice is to put the name that is on your earliest official record, which is usually our birth registration. In your case, this is your birth name, not your father’s.